Ian Goldin & Tom Lee-Devlin, Age of the City: Why Our Future Will Be Won Or Lost Together, Bloomsbury, 2023.

This is not a review (there’s a good one here) nor a summary (there is an article-length version of the argument here and a video presentation here). Instead what I’m doing here is plundering this recent book by Goldin and Lee-Devlin purely for material that could be helpful to church planters and others interesting in understanding the social dynamics of London.

- The complexity of London

- The sheer size of London

- The economic, social and geographic divide

- The changing breathing of London

- The different psychologies of inner city and suburban

- How is post-Covid remote working changing things?

- How are the demographics likely to change?

The complexity of London

“The urban world is a complex system” (p.168). We shouldn’t assume we understand it and still less that we can predict how changes in one variable will affect other variables.

The sheer size of London

Depending on which definition you use and which data sets you use, the population of London is somewhere between 8.9 and 9.8 million. This is not exceptionally large by global standards. China has plenty of cities that are larger and is likely to grow a stack more over the coming decades. But London is 10 times the size of Liverpool. And vastly greater in scale than anything humans have experienced until very recently.

“About [190 people can fit into a single London tube carriage (1500 on the whole train)], greater than the size of a typical medieval village” (p.135).

Around 600,000 people use the Northern Line each day.

London is a place to disappear into the crowd.

The economic, social and geographical divide

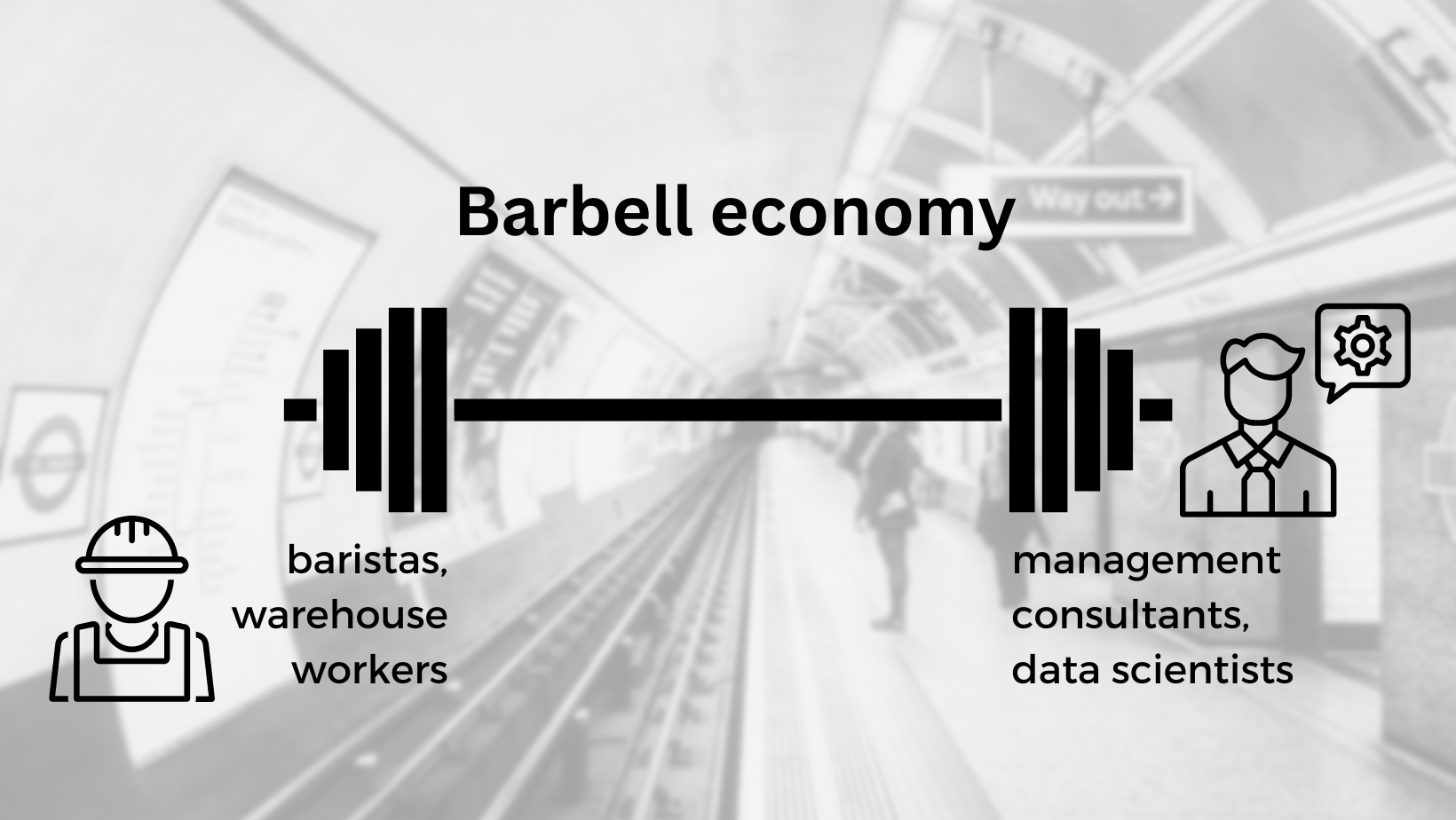

“A bar-bell shaped economy has emerged, characterized by high-paid knowledge jobs… on the one hand and low-paid service jobs… on the other” (p.8). What we’ve lost is the middle-income manufacturing and middle-management jobs in the middle.

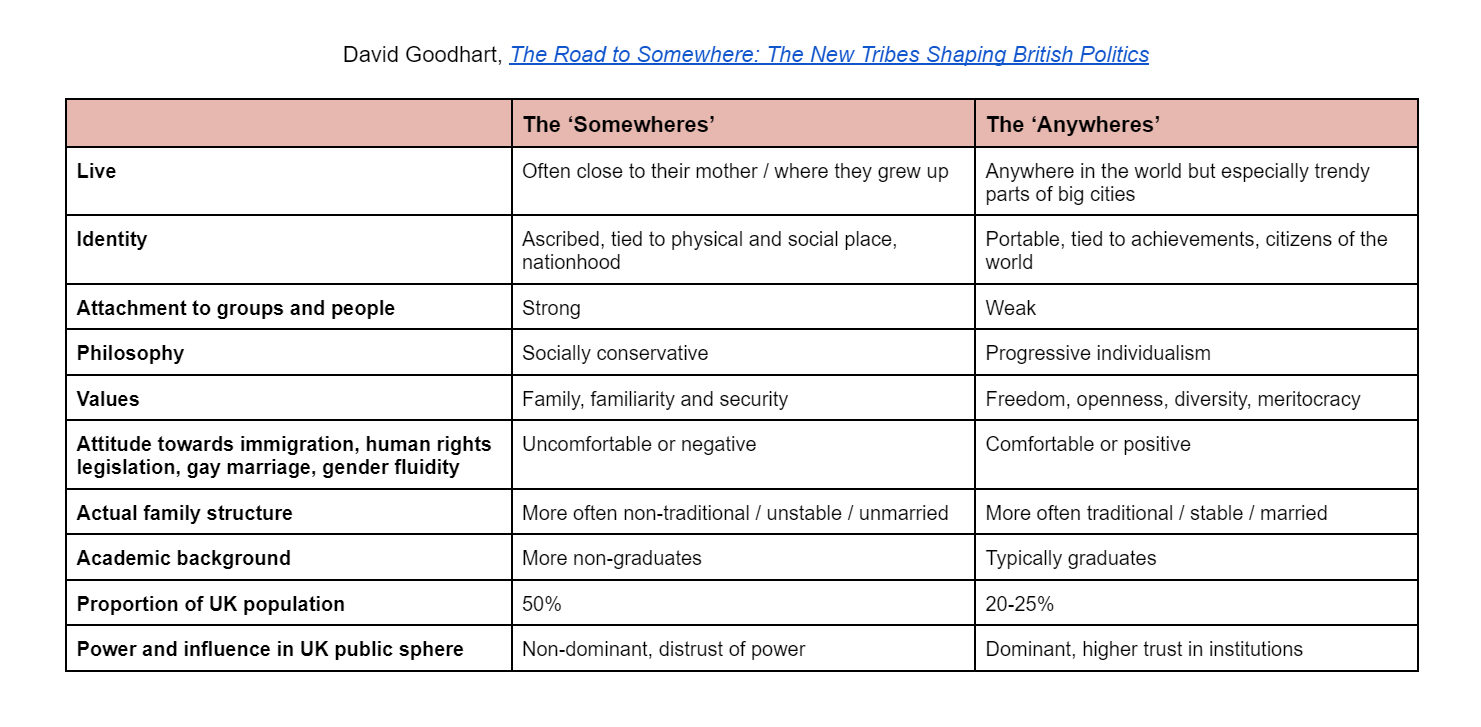

This corresponds roughly with David Goodhart’s categories of ‘Somewheres’ and ‘Anywheres’ living in different worlds. “The fact that many educated elites in London knew no one who had voted for Brexit… was the ultimate testament to how disconnected they had become from their wider societies.” (p.9).

And this economic and social divide also maps onto the geography of London. Note how the boroughs voted on Brexit.

“The great inversion” (p.66) in recent decades has meant “high-paid knowledge workers have returned to inner cities [gentrification]… while low-paid service workers have been relegated to distant commuter zones where much of their free time is absorbed either stuck in traffic or navigating whatever patchwork of public transport options they have available to them.” (p.170)

This socio-economic-geographic divide had been compounded in recent years a) through Covid lockdowns: “learning losses were 50 per cent greater in secondary schools in disadvantaged neighbourhoods” (p.134); and b) through the increased tendency for people to chose partners with the same education level and political views: “In the 1970s, roughly 50 per cent of individuals with a bachelor’s degree were married to a spouse who also held a bachelor’s degree. Today, the figure is closer to 70 per cent” (p.48).

However, it’s not quite as simple as inner-gentrifying-professionals / outer-commuting-service-class. For one thing there is a flow from inner to outer, and that flow is changing…

The changing breathing of London

Richard Perkins has talked about how there is a rhythm of London breathing people in and exhaling them. Similarly Goldin & Lee-Devlin describe: “While many teenagers leave the city… to attend university, they return after their degrees are completed, and bring with them many more young adults from across the country. As a result, net migration into inner London flips from negative to positive for adults in their early-twenties, and continues rising into the mid-twenties [and in the last two decades the amount of net migration into these inner boroughs by those in the mid-twenties has nearly tripled (p.73)]. After that if begins to taper off and eventually turns negative again as adults have children and leave for the outer suburbs and commuter towns” (p.72). Significantly, the point at which this second flip happens has increased by a whole decade since the early 2000s, “from age 34 to age 44”(p.73) driven by shifts to a later age of childbearing and even later age of marriage.

As well as the exhale from inner to outer boroughs happening later, London’s breathing is becoming more laboured in general. Movement around the city is becoming increasingly difficult as the ratio of average house price in London to average income in London has gone from roughly 3.5 in the mid-1990s to an astonishing 11 times today (p.51). Plus, with dual-income households becoming the norm, “relocating now typically involves two job searches [to co-ordinate], each bringing with it a high degree of uncertainty. And while one half of a couple may be struggling to find work, the other half may be quite happy where they are” (p.50).

The different psychologies of inner city and suburban

Inner urban high population densities and mass use of public transportation (i.e. tubes and buses) often, it is argued, encourage a more positive attitude towards diversity. “What may feel unfamiliar and threatening when encountered the first time gradually begins to feel normal with each new exposure, and with time can even come to be seen as a valuable contribution to the rich tapestry of a varied life” (p.106).

In contrast “Lewis Mumford once described suburbanization as ‘a collective attempt to live a private life’” (p.106). Architecturally, suburbia is about conformity and sameness rather than the individually sought by the ‘bourgeois bohemian’ of Shoreditch (p.69-70).

Suburbia trades ‘proximity for space’ and ‘serendipitous connection with privacy’. “What cars have brought is privacy and choice. They have made it possible for the majority of urban populations to move out to the suburbs, where they can live in large homes in quiet cul-de-sacs with their own backyards… [and] shuttle from destination to destination without ever having to encounter anyone not of their choosing… And time spent commuting limits our ability to engage with our community – ten minutes extra daily commuting time reduces involvement in community affairs by an average of 10 per cent” (p.106).

There are challenges for church planters both in engaging the crowded pavement and the empty pavement; extroverted individualism and introverted individualism.

How is post-Covid remote working changing things?

A key argument of the book is that remote working is not going to be the death of the city. “The great paradox of modern globalization: that declining friction in the movement of people, goods and information has made where you live more important than ever” (p.xiii).

“Creativity still thrives on physical interactions… Most jobs are still apprenticeships” (p.xiv). And not just trades like carpentry: “most modern knowledge work relies heavily on sustained informal coaching. It is difficult to replicate the casual feedback after a meeting or the quick corridor question when working remotely” (p.86). Physical interaction is needed to build the necessary rapport with senior colleagues and not be ‘forgotten about’ (p.87).

And in any case, “most people cannot do their jobs remotely. It is an option for only about one in three workers in rich countries” (p.6). “In the United Kingdom, it is estimated that fewer than one in ten workers in the bottom half of the income distribution can perform their jobs remotely” (p.143).

And, as many of us have noticed, remote working often makes us less productive because of the “increase in the time spent in meetings and sending emails. Being physically co-located with colleagues in an office produces a comparatively fluid system of communication… A brief dialogue can eliminate a time-consuming email exchange… Uber noted a 40 per cent increase in meetings after the pandemic struck and staff started working remotely, with average number of participants attending each meeting rising by 45 per cent” (p.85).

Positively, “our commutes play an underappreciated role as a psychological barrier between our work and personal lives” (p.84).

So place is still important, people will not be leaving London en masse to work from a coffee shop in Scotland or a beach in Spain. What is happening is – a) centralisation of office working and b) hipsturbia…

Instead of (as was predicted a couple of decades ago) large companies going for a dispersed model of several out-of-town satellite offices, what has actually happened has been a centralisation, consolidation and “flight to quality’ (p.90). With workers only coming to the office twice a week, companies have given up on underused offices in places like Croydon and instead invested in prestige central London offices. Google’s $1BN new London office (p.91) may be the most impressive example but is part of a wider trend.

Meanwhile, the suburbs where these workers live for the rest of the week are also becoming more urban:

“The shift towards hybrid working also presents an opportunity to bring the urban back into suburban. As knowledge professionals spend less time in central business districts and more time in their neighbourhoods, they will bring with them more demand for trendy lunch spots, fancy gyms and other such services… The term ‘hipsturbia’ has recently emerged to describe young and vibrant mixed-use districts in suburban areas” (p.92). “Constructing terrace houses and… mid-rise developments near to these precincts… [provides] a critical mass of customers within easy walking or cycling distance” (p.171).

I can see that happening in my own suburban neighbourhood with a growing rash of gyms, independent coffee shops and 4 storey blocks of flats replacing old pubs, light industrial and low density housing.

How are the demographics likely to change?

Predictions are complicated and by definition uncertain but it is very likely that London will top 10 million at some point in the next two decades. The population will also shift older (London is currently a particularly youthful city) with fewer children (primary schools in London expecting a drop of 52,000 by 2028) and a 60% increase in over 65s to 16% of the total by the 2040s.

The diversity of London is well known. “While London contains 13 per cent of the UK’s population, it is home to 35 per cent of those living in the UK who were born abroad” (p.49). That may well need to increase even further to replace the gap in workers created by falling birth rates in the UK and in London in particular (the total fertility rate in London dropped to its lowest level on record in 2022 at 1.39 (ONS)). Another factor (less frequently talked about) that could drive immigration higher is climate change. Goldin and Lee-Devlin describe a conceivable nightmare scenario where the 2 billion people who live in the basins fed by rivers originating in the Himalayan glaciers are forced to move as those glaciers shrink, the rivers dry up and there is massive loss of land fertility. “Accepting one million Syrian refugees destabilized European politics in a way few expected. Migration as a result of climate crises will be orders of magnitude greater” (p.11).

In the more distant future, if the Lord doesn’t return in the meantime, the population of the whole globe will start to decline/collapse (around 2080??). At that point there is no propping up of London through immigration. An aging population runs out of workers, carers, innovators and police. The economy and house prices crash, vacancy increases, crime increases, small businesses can’t be sustained, social division increases. If you want to see what that could look like, check out the story of Detroit, once one of the richest and largest cities in the world which lost over 60% of its population from 1950 to 2010 (and another 8% 2017-2024).

Sorry to leave things on a bleak note! Though often the bleakest of times can have the most Kingdom opportunities…

Photo of Detroit by Kyle Berryman on Unsplash

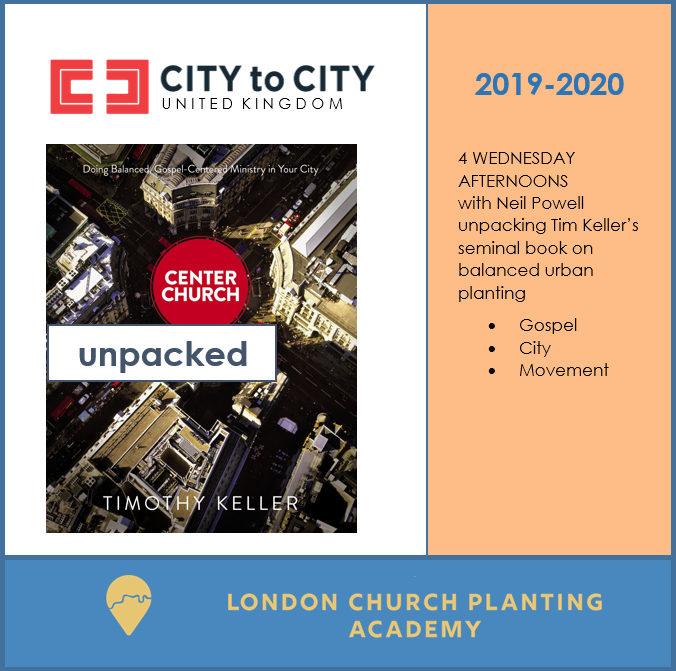

We’re very grateful that Neil Powell, senior pastor of City Church Birmingham, co-founder and convener of 2020 Birmingham and London director for City to City UK, will be coming to unpack Tim Keller’s Center Church for the London Church Planting Academy on 4 Wednesday afternoons:

We’re very grateful that Neil Powell, senior pastor of City Church Birmingham, co-founder and convener of 2020 Birmingham and London director for City to City UK, will be coming to unpack Tim Keller’s Center Church for the London Church Planting Academy on 4 Wednesday afternoons: